A Visualization of Europe's Non-Bubbly Economy

The Draghi task force has a lot of work ahead of it

While eating a lunch of Thanksgiving leftovers last Friday I read that the EU has created a task force to act on the findings and recommendations of Mario Draghi’s excellent report on EU competitiveness in the second machine age (my title, not his). Draghi made an unignorable case that growth and competitiveness are fading in Europe, creating an “existential crisis” for the region. European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen apparently agrees. According to Politico, last week she “announced the main initiative of the next five-year term will be a "competitiveness compass" to close the innovation gap with the United States, decarbonize the EU economy and increase its economic independence, with each commissioner told to contribute to these goals.” This post visualizes that daunting task.

I wrote earlier here about how well Draghi laid out the challenges facing the region. I had my problems with the report's recommendations, but not with its presentation of the existential crisis. The Draghi Report combines broad descriptions of the problem with well-chosen, hard-hitting statistics. For example, I thought I grasped how big the differences were in the US vs. EU innovation ecosystems but was unaware that, as the report points out, Europe lags in VC funding at every stage by about a factor of five.

Of all the chiffres justes in the report, though, the ones that most startled me were in this sentence: “there is no EU company with a market capitalisation over EUR 100 billion that has been set up from scratch in the last fifty years, while all six US companies with a valuation above EUR 1 trillion have been created in this period.”

This sentence rises not to the level of art or literature, but instead showbiz: it leaves the reader wanting more. It tells us that Europe has no from-scratch companies founded in the past fifty years — let’s call such companies arrivistes — worth a hundred billion, but is silent on just how many US arrivistes are over that bar.

Also, how many are below that bar, but still sizable? If we lower the threshold by a factor of 10, what do we learn? How many arriviste European companies are worth at least $10B (I’m switching from euros to dollars here)? And what's the equivalent number in the US? Questions like these motivated the crack research team here at Geekway Labs to dig into the numbers and see what a fleshed-out comparison of the arrivistes on both sides of the pond looks like.

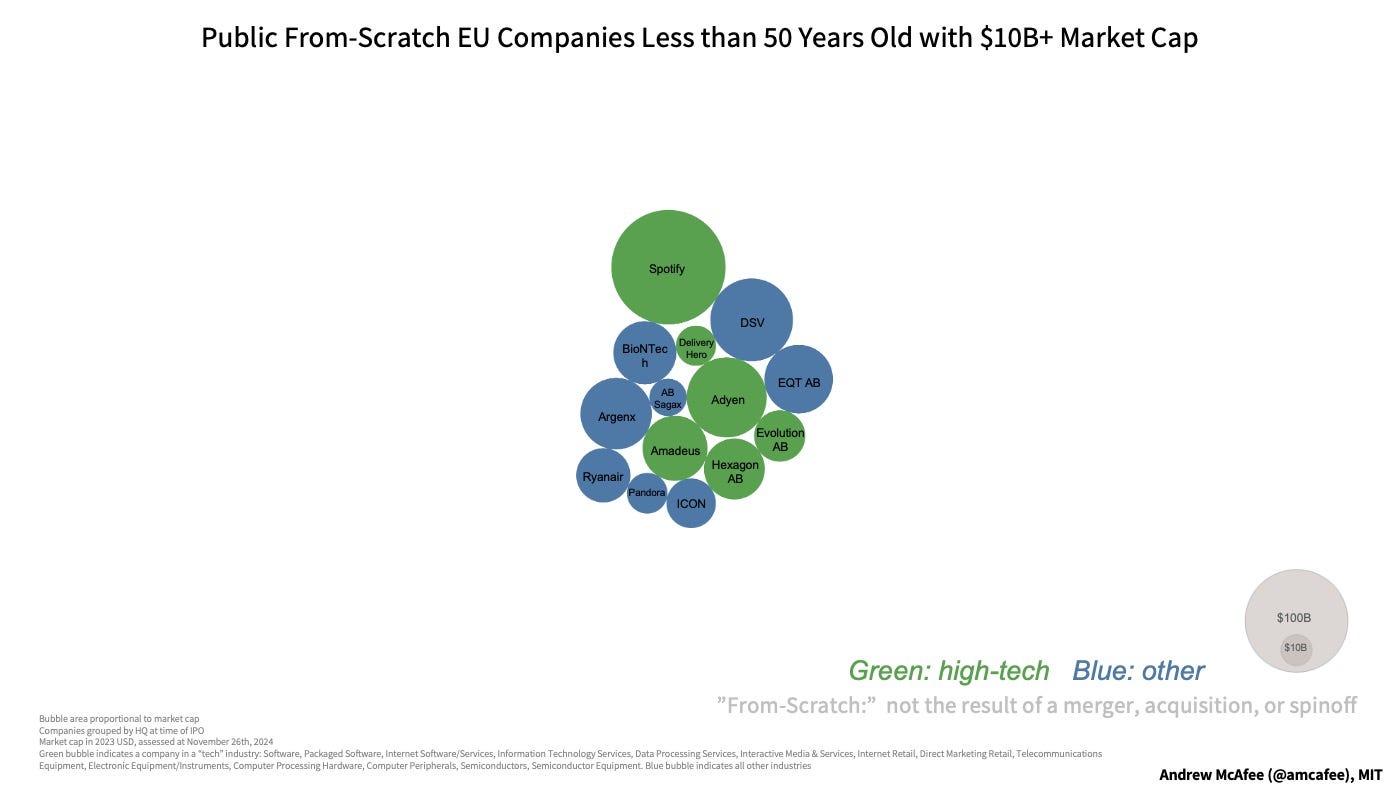

Like the rest of the Draghi report, it's not a pretty picture for Europe. Here's the European half of the picture, with each arriviste worth at least $10 billion represented by a bubble, the area of which is proportional to the company’s market cap. As is convention around here, green bubbles indicate companies in digital high-tech industries:

When assembling this visualization, we followed Draghi's definition of a from-scratch company. ““From scratch” refers to starting a company from its inception as a new entity, rather than through mergers, acquisitions or spinoffs from established firms.” We also considered only publicly-traded companies (since the report specifies “market capitalisation,” not private valuation). The picture above therefore doesn't include a bubble for Celonis, a private German enterprise tech company valued at $13B in its last funding round. According to CB Insights, that's Europe's only “Decacorn,” or private, VC-backed startup worth more than $10 billion.

We found 14 EU arrivistes worth at least $10B (But we may have missed some, even though we combed through the Factset data pretty carefully; here are our data. If you know of a company that meets the Draghi criteria but is not in the picture above, please let me know.). The total market cap of this continental quatorze is about $430B.

On one hand, $430B is a lot of money. On the other, it's less than half of a Tesla today1, and less than 1/8 of an Apple or Nvidia. The biggest American arrivistes are staggeringly big.

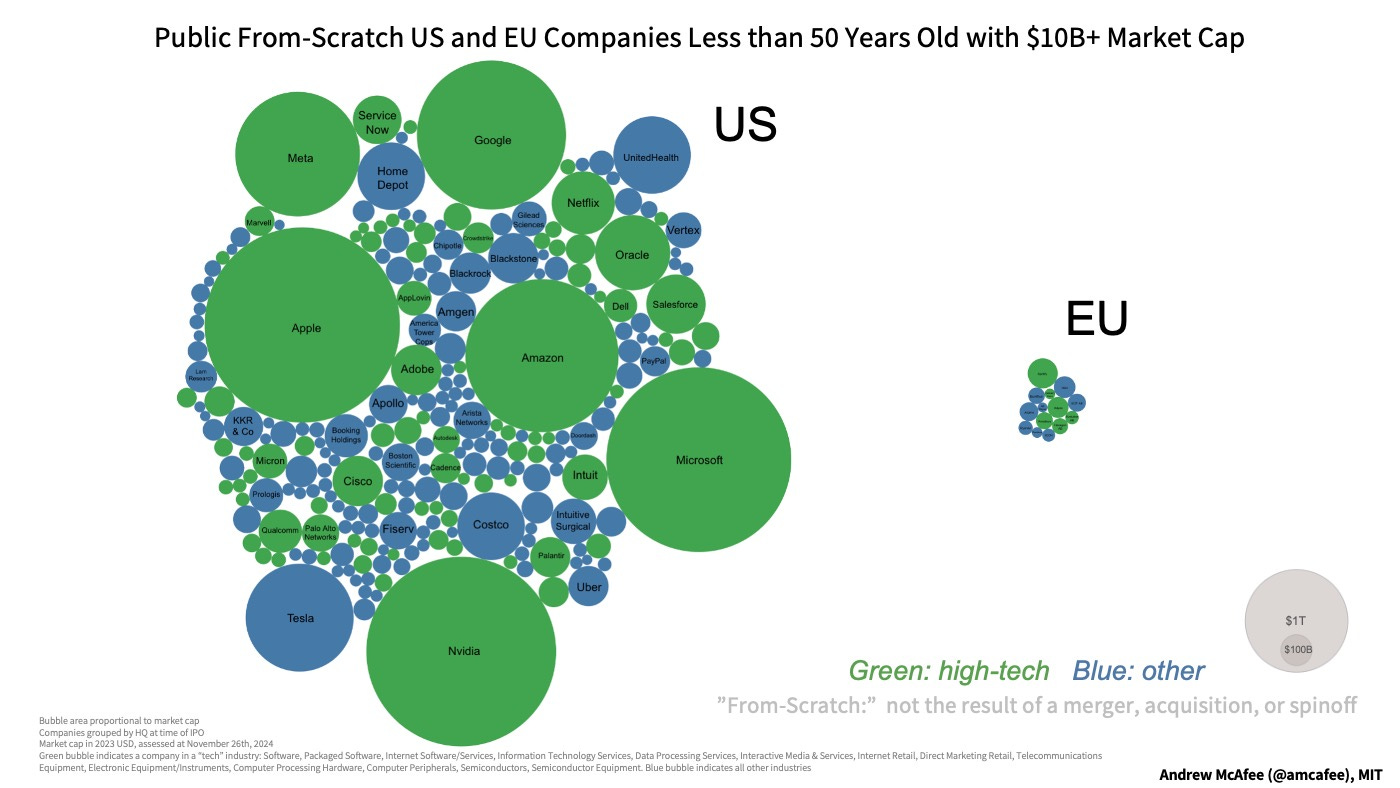

As Draghi points out, it's not great that Europe doesn't have any companies near their size. But it's even worse that compared to the US, the EU has so few chances at creating the next giant arrivistes. I feel like I should give a trigger warning at this point to Europe's tech and competitiveness boosters: the data visualization they're about to see is not kind to their hopes and dreams. Here’s the Euro quatorze again, this time next to the equivalent US cluster: all American public arrivistes worth at least $10B:

The US has a large and variegated population of valuable young from-scratch companies. The EU simply doesn’t. The American population of arrivistes worth at least $10B is collectively worth almost $30 trillion dollars — almost 70 times as much as its EU equivalent.

When I talk about the above facts and figures with European audiences, I typically hear two explanations for the huge disparity. They both stem from the fact that the U.S. is a gigantic market unified both by institutions and language, while Europe is not. The EU is more fragmented because of the large number of languages spoken and the patchwork of laws, legal systems, and so on.

Both of these things are certainly true, but do they fully explain the gap? Yes, Europe doesn’t have a single language, but it has several that are spoken by many millions of potential customers. German, for example, is spoken by about 130 million people in the EU (and is the first language of about 85 million), French by 110 million (65), Spanish by 75 (40), and Italian by 72 (58). Heck, about half the people in the EU say they speak English proficiently, so even technologies that ignored the local tongue altogether could conceivably find a huge audience. And with the science-fiction-become-reality automatic translation tools widely available today, for how much longer will language barriers stand as plausible barriers to technology use?

The EU’s legal situation is a much bigger problem than its linguistic one. As Draghi says right on page 2 of the report, “innovative companies that want to scale up in Europe are hindered at every stage by inconsistent and restrictive regulations.” The “inconsistent” part is bad, but I think the “restrictive” one is worse. The EU is putting too many restrictions and requirements on its young tech companies, as I described here. Expecting them to catch up to their US counterparts while laboring under these constraints is like expecting US soccer players to outplay their European rivals while wearing weight vests, blindfolds, and clown shoes.

The company, not one of its cars.

4 of the 14 companies you found are Swedish. And I think that Akelius Residential Property AB https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Akelius also belongs on the list, but I haven't read the report so maybe there is a different reason it was excluded. Not bad for a country of 10 million people. I do not know if the rest of Europe has the problems we have, but in Sweden we have a great many small companies, a few very large ones, and very few that are moderately sized. So if you are a small company and are growing to the point where you need more management, you often cannot find people who have experience in managing in firms that are at the 1000-2000 employee size, and trying to grow. They don't exist. And you end up being better off forking the company into two smaller ones because you do know how to find people who can manage well at the smaller size. This works if you only care about the domestic market. But what if your ambitions are greater?

When all goes well, and it is time to expand to the rest of Europe, Swedes all discover the problem you have collaborating and managing despite profound differences in managerial style and business culture. And this often defeats the expansion. Sweden is an exteme outlier in business cultures, particularly in the flat-egalitatrian vs layered-hierarchical dimension. You cannot expect French or German workers to behave like Swedish ones. They need more direction, and to be lead more. But Swedish managers sent to France and Germany often have no clue how to provide this, or often even have no understanding that this is the problem, and keep trying to get their workers to show more initiative, and stop being so deferential. (There is more understanding that this is the problem these days.) I think that this is the sort of business cultural differences, far more than the various languages, which makes it harder to grow businesses in Europe.

Some European mergers between companies that come from different countries have been very successful. And larger companies vaccuming up smaller ones in the same sector all across Europe has often worked out for the larger companies -- people interested in this can read a history of ABB, which will not make the Draghi list because it was founded in 1988 by the merger of 2 firms, Sweden's Allmänna Svenska Elektriska Aktiebolaget (ASEA) and Switzerland's Brown, Boveri & Cie. They are now the leading company in industrial robotics, with 21% of the market. Their nearest rivals have 9%. see: https://www.statista.com/chart/32239/global-market-share-of-industrial-robotics-companies/ This is the sort of success we want, so it would be nice if we could find out how ABB did it They have a market cap of 105.66 Billion USD, but somehow aren't on the https://companiesmarketcap.com/tech/largest-tech-companies-by-market-cap/ list. Oversight? or are there rules about what goes into that list that I am unfamiliar with, and so misunderstood? . Assa Abloy is another founded less than 30 years ago by an inter-country merger success. Maybe this is an easier way to succeed, rather than trying to impose your culture on other nations?

I don't think this changes the overall story significantly, but worth noting that Microsoft and Apple are 49 and 48 years old, while SAP (the largest EU tech co.), is 53 years old, just falling on either side of the 50-year cutoff.

In a couple of years, the graphic would be somewhat different (not substantially different, but not negligibly different either).

Conversely, if SAP were added, the EU bubble group would be 75% larger (+ $320Bn).