Jack Welch's Theory of Leadership: A Model for Failure in the 21st Century

Why a company obsessed with winning often doesn't

Let’s kick off the topic of today’s post by talking about a word that I’m pretty sure has never appeared in print near Welch’s name without the prefix “in-.” That word is vulnerability.

I used to dislike hearing it in discussions of behavior on the job.1 I often couldn’t make out exactly what vulnerability’s advocates were talking about, but it seemed like they were saying that it’s OK to spend a decent chunk of the workday talking about what wasn’t going great for you, seeking solace and support from your colleagues, and taking the time that you needed to get to a better place.

I had a few objections to this dumb caricature I’d created for myself perspective. First, none of that felt like what you were getting paid for. Second, you were also taking up other people’s time. Third, you were setting a negative example; if Andy’s treating his job as paid therapy, why shouldn’t I? This last one felt like the most important reason not to foment vulnerability at work: it could be damaging to cooperation, which is one of our species’ superpowers.

Cooperation and Its Kryptonite

We humans are Earth’s best cooperators in large part because we expect reciprocal altruism. I show up with my hammer to your barn raising because I expect you to show up with your saw to mine. Our brains keep track, mostly subconsciously, of favors done and expected. When those expectations are largely met, reciprocal altruism continues and our superpower of cooperation does its thing. We raise barns, launch rockets, and accomplish other goals that are difficult to impossible for any individual.

But human self-interest can screw up human cooperation. We’re unique in our ability to cooperate, but we’re far from unique — we’re just like every other living thing — in our self-interest; we want to improve our individual cost/benefit ratio. Slime molds, scorpions, and CEOs alike want to increase their odds in the constant struggle of existence by doing less of the struggling.

This desire to improve the cost/benefit ratio of existence is in head-on conflict with reciprocal altruism, for the simple reason that the “altruism” part is costly. Going to your barn raising means that I can’t milk my cows, tend my crops, or do other things that day that benefit me and my progeny.2 I therefore have a lot of incentive to get you to come to my barn raising but avoid having to go to yours later. I have ample incentive, in other words, to shirk or freeride. So do you.

You didn’t like that last sentence, did you? You probably immediately said something to yourself like “I’m no shirker!!” That strong instinctive reaction reinforces how important cooperation is, because it shows us how seriously we humans take any accusation that we’re not cooperating as expected. Our brains strenuously object to the accusation of freeriding and tell us to fight back against it. But as we just discussed, our brains also constantly scan the environment for opportunities to freeride. We’re complicated that way (and in many other ways).

Because our brains weren’t born yesterday3 they also constantly scan the environment to see if anyone around them is freeriding. And they’ll share what they observe. If I stop showing up at barn raisings in our small Amish community without a good reason, word will quickly get around. Gossip will spread, my reputation will suffer, and people will stop coming to my barn raisings, crop harvests, and quilting bees. Gossip and reputation are key mechanisms for maintaining cooperation in human communities.

So our brains have a tricky assignment: they have to improve our cooperation-related cost/benefit ratio while avoiding a reputation for shirking and the attendant gossip and reputation damage that comes along with that reputation. A brilliant solution, and one that more than a few brains have come up with, is to weaponize other people’s altruistic tendencies so that they feel bad for us as we shirk instead of mad at us as we shirk. How? By making others believe, incorrectly, that we can’t help out because we ourselves need help. This flavor of shirking is called malingering.

I bet you really didn’t like that word. Malingering is considered an odious offense exactly because it’s such a perversion of cooperation. In the US military, for example, it’s punished harshly; dishonorable discharge, forfeiture of pay, and confinement for up to ten years.

I want to be bold-font clear here: It is not the case that everyone who says to their colleagues “I’m going through a rough stretch” is a malingerer. I’ve said it more than once, and have every time been grateful for the care, help, and support I’ve received. It’s also not the case that all malingering is conscious scheming. A lot of it, I believe, originates below the level of conscious thought (where a lot of everything we do originates). All I’m trying to do is explain why the talk I was hearing about the importance of vulnerability at work was making me uneasy. It seemed to me that such talk could open up an avenue for malingering.

And that avenue could get crowded. If you believe that the people around you are shirking, it’s natural to feel like a sucker for not joining them. Why should I be altruistic if it’s not going to be reciprocated? Why should I cooperate if everyone’s just going to take advantage of me? Once enough people in a community feel that way, barns stop getting raised. And that’s a shame; it’s a deactivation of one of our human superpowers.

To keep that superpower going, it seems smart to cut down on the malingering type of shirking by not encouraging vulnerability in the workplace. Following this approach doesn’t mean driving your people like rented mules. It just means establishing a norm that you show up at work to… work. Be part of the cooperative enterprise you’ve signed up for. If everybody expects everybody else to do that, the thinking goes, and everybody believes that no one has the easy out of malingering, then the cooperation flows long and strong.

But this too can easily go wrong. It can lead to a social situation that’s at least as bad as the cynicism that comes when everyone shirks and malingers. To see how, let’s revisit the career and management philosophy of Jack Welch, the most acclaimed American CEO of the 20th century. And the mess he left behind.

What Hath Jack Wrought?

It’s still hard for me to believe how far General Electric has fallen.

It was the last non-tech, non-Silicon Valley company held up as the go-to example of American industrial and managerial prowess. It made everything from light bulbs to jet engines, but what it really made was money, and it made it steadily year after year. Throughout the late 1990s it was the most valuable company in the world.

GE also made people who knew how to make money. The company believed fervently that through the training and career progression approaches it pioneered it could mold people into general managers, who are kind of like the survivalists of the business world: plop them into any environment, and they’ll figure out how to make a go of it. David Gelles, author of a book about Jack Welch GE’s CEO from 1981 to 2002, noted that

For a time in the early 2000s, five of the top 30 companies in the Dow Jones industrial average were run by men who had worked for Mr. Welch. “That’s why they got hired,” said William Conaty, G.E.’s longtime chief of human resources. “Because they had the playbook. They had the G.E. tool kit. And boards back then thought that was the answer.”

Many GE alums talked about Welch with language lifted from a North Korean style guide. Jeff Immelt, who took over Welch’s job, reflected the consensus view by calling him “the best leader of the previous century.” David Zaslav, who worked at NBC when GE owned it, went a good bit further: “Jack set the path. He saw the whole world. He was above the whole world.”

Welch was a working-class kid from a small town in Massachusetts who made many believe that any working-class, small town kid could become a big boss in the rugged arena of American (nay, global) free enterprise if they just worked relentlessly and hewed to a few simple rules. These is no mention of, and no place for, vulnerability in these rules:

Take charge. As he put it, “Good business leaders create a vision, articulate the vision, passionately own the vision, and relentlessly drive it to completion.” Career progression at his GE was all about taking on bigger assignments over time and delivering results, not excuses. The aphorism most closely associated with Welch (to the point that it’s the title of a book of his leadership lessons) is “control your destiny or someone else will.”

Stay positive. Welch radiated optimism and expected others to share the can-do vibe. In many interviews he stressed that he welcomed candor and debate, but he also wrote in his book Winning (coauthored with his wife Suzy Welch)

[Disruptors] are individuals who cause trouble for sport - inciting opposition to management for a variety of reasons, most of them petty.

Usually these people have good performance - that's their cover - and so they are endured or appeased…

Disrupters are a personality type. If that's the case, get them out of the way of people trying to do their jobs. They're poison.

In Jack Welch’s world, you gotta watch out for good performers who rock the boat by disagreeing with management.

Strive to win and minimize losing, just like the book title says. One of Welch’s most famous directives, issued soon after he became CEO, was that throughout the company every business unit had to be on top, or at least close. It had to be #1 or #2 in its market to avoid being sold, closed, or “fixed.” Being on top of the heap also mattered for people at GE. Welch instituted a performance review system called “stack ranking,” which is very much what it sounds like (although Welch preferred the term “vitality curve.”). At each performance review, the people constituting the bottom 10% were in real danger of losing their job. Welch, meanwhile, had an epic winning streak. Earnings report after earnings report, he stuck the landing without a wobble. Over one stretch, GE met or beat analysts’ earnings forecasts in 46 out of 48 quarters, and of those 46, 41 matched the forecast to the penny.

So much Winning. So little vulnerability

On Continuing to Not Listen to Chris Argyris

The three boldface rules above weren’t laid down by Welch himself. They instead come from Chris Argyris, who I think is one of the most important management scholars ever. He’s largely forgotten now, which is a shame; he did deep and original thinking to understand why so many companies lose their way and descend into dysfunction and underperformance.

Argyris was interested in what he called the “theory in use” at an organization. This is not the same as the “espoused theory” — the things a company and its leaders say about how the place operates in annual reports, CEO speeches, motivational posters, and so on. The theory in use is how the place actually operates. I don’t know if Argyris would agree4, but I think “norms” is a close synonym for “theory in use.” Norms are behaviors that a group’s members expect from each other and maintain via community policing.

The three bold rules above — take charge, stay positive, and strive to win and minimize losing — are my slight edits on the norms / theory in use Argyris found at most companies he studied and worked with in the 1970s, 80s, and 90s. He called it “Model 1.”5

The 21st-century business leader who most reminds me of Welch in his fondness for Model 1’s norms is Steve Ballmer, who was Microsoft’s CEO from 2000 to 2014. Ballmer met Bill Gates when they were both Harvard students, and dropped out of Stanford Business School to join Microsoft in 1980.

His intensity, drive, and passion were incandescent. He made Welch look like a clock-watching salaryman. And he lived the three rules listed above. Ballmer took control, radiated meme-generating positivity (at such volume that he needed surgery on his vocal cords), strove to win, and hated losing more than Shoresy.

His conference speeches were not noted for equivocation; "All in, baby! We are winning, winning, winning, winning" is a representative pull quote from 2011. According to filings in a court case, when he learned that Microsoft was losing — in this case a top executive to the hated Google — Ballmer threw a chair across a conference room and shared some thoughts about the competition and its leader: “Fucking Eric Schmidt is a fucking pussy. I'm going to fucking bury that guy, I have done it before, and I will do it again. I'm going to fucking kill Google.” LLM1, the OpenAI GPT I just made up to dispense pure Model 1 advice, is trained largely on Ballmer’s every recorded utterance as CEO, along with a judicious smattering of Welch’s.

Now here’s the thing

Now here’s the thing. We can debate whether Ballmer went a bit too far in that conference room. We can ask, as the SEC did, whether GE’s chef’s-kiss earnings performance was due in (large?) part to GE Capital’s opacity and suitability as a slush fund. We can question if Welch, who was worth about $900 million when he retired (which, back then, was real money), really needed GE to pay for courtside Knicks tickets and four country club memberships as part of his pension.

But Argyris teaches us that all of that misses the most fundamental point. The most fundamental point is that Model 1 is a lousy way to run a modern company.

Not because it scares away sensitive souls. Not because it too often descends into men shouting at each other. Not because American capitalism needs to become more accommodating to people who didn’t play high school football.

All of those things could be true. But what’s also true, Argyris said, is that Model 1 causes a particular kind of slow-motion train wreck under the right circumstances. It’s a train wreck that’s going to unfold at Model 1 organizations even if they are full of ex-linebackers.

As I write in The Geek Way (TGW):

Who could argue with [Model 1]? Maybe that’s not the right playbook for teaching preschoolers or rehearsing an avant-garde play at a collectivist theater troupe, but it sure looks right, or at least close to right, for getting things done in the business world, no?

With thunderclap simplicity, Argyris said no. And then he explained why.

The core problem, which crops up over and over again in all kinds of ways, is that Model 1 produces defensive reasoning

How could it not? If you’re living in a Model 1 environment of course you’re not going to want your project cancelled or your headcount reduced. Those acts are the exact opposite of you taking control. As is letting the organization pivot away from the product development effort or go-to-market strategy you’ve been championing. Entertaining arguments that the proposed merger is a bad idea, or that customers aren’t loving the new offering, isn’t staying positive, it’s “loser talk.” Under Model 1 changing course is a rare event because it feels like losing instead of continued striving to win.

Argyris was a soft-spoken, kindly person who dropped truth bombs. I often heard him say, without any hint of wiseassery, something like “people under Model 1 come across as defensive because… they’re defending all the time.” As he wrote, under Model 1 strength means “Advocate your position in order to win. Hold your own position in the face of advocacy. Feeling vulnerable is a sign of weakness.”

Model 1 might not get you into trouble if and when vigorously defending the status quo and punishing all departures from it is a good business strategy. Argyris likened it to a (20th century) thermostat, which has a very simple job: DEFEND THIS SINGLE TEMPERATURE. But when things get more complicated — when, to continue the analogy, sensors, processors, networks, and software enable smart thermostats — our inherently defensive thermometer becomes obsolete, and eventually gets swapped out.

As you might have heard, sensors, processors, networks, and software have all proliferated and progressed a lot in the 21st century. They’ve brought us into a second machine age,6 and I believe we’re still underestimating how different this age is from the late 20th century — from the sunset years of the Industrial Era. More on that topic soon.

Globalization has reshaped the business world over the last quarter century but digitalization has reshaped it more. I’ll soon share some data here7 showing how deep the digitalization has been over the course of the 21st century, and how much the business world has changed over that time. Pssssssst - those two phenomena are linked.

Following Model 1’s norms during a time of deep change is a bad idea because Model 1 is all about not making deep changes to a company. Defensiveness is Model 1’s core reality, no matter what leaders say (or, indeed, actually want). When serious change is afoot, in short, Model 1 leads to Day 2.

“Day 2” is a Jeff Bezos coinage. From TGW:

Since 2010 Jeff Bezos has closed all of his shareholder letters with the words “It’s still Day 1.” The 2016 letter opens with an explanation of what this means:

“Jeff, what does Day 2 look like?”

That’s a question I just got at our most recent all-hands meeting.

I’ve been reminding people that it’s Day 1 for a couple of decades. I work in an Amazon building named Day 1, and when I moved buildings, I took the name with me. I spend time thinking about this topic.

Day 2 is stasis. Followed by irrelevance. Followed by excruciating, painful decline. Followed by death. And that is why it is always Day 1.

To be sure, this kind of decline would happen in extreme slow motion. An established company might harvest Day 2 for decades, but the final result would still come…

Exhibit 1 of Day 2 is GE’s share price performance over the course of the 21st century up to the day in June of 2018 when it was delisted from the Dow Jones Industrial Average:8

Exhibit 2 is Microsoft’s share price from the same start date to the day Satya Nadella took over from Ballmer in 2014:

There’s a lot of statis and decline on display in those charts. As I write about Microsoft in TGW:

Like other large technology companies Microsoft saw its share price plummet when the dot-com bubble burst in March of 2000. But in the years that followed, the company didn’t bounce back. Instead, it seemed to lose its ability to innovate, join the trends that were reshaping the high-tech industry, or impress investors. Microsoft fell far behind on Internet, mobile, and cloud computing technologies. Windows and Office continued to generate revenue and profits, but little the company did generated much excitement. As it stumbled along year after year, Microsoft became a farce to many observers and a tragedy to its investors. Its share price was about as flat as a corpse’s EKG from the start of 2001 through the end of 2012. At the end of that dozen-year period of enormous innovation in digital industries and some of the fastest growth the global economy has ever seen, the verdict of the market was that Microsoft was less valuable than it had been at the turn of the millennium (after taking inflation into account), despite having spent well over $80 billion on research and development.

Since the end dates of the above charts, things have turned around for both GE and Microsoft. Their current CEOs deserve much of the credit. At GE, Larry Culp (the first outsider to run the place) has slashed debt, sold off large businesses, and returned the company to its core business of making things. He’s a huge fan of continuous improvement and lean manufacturing.

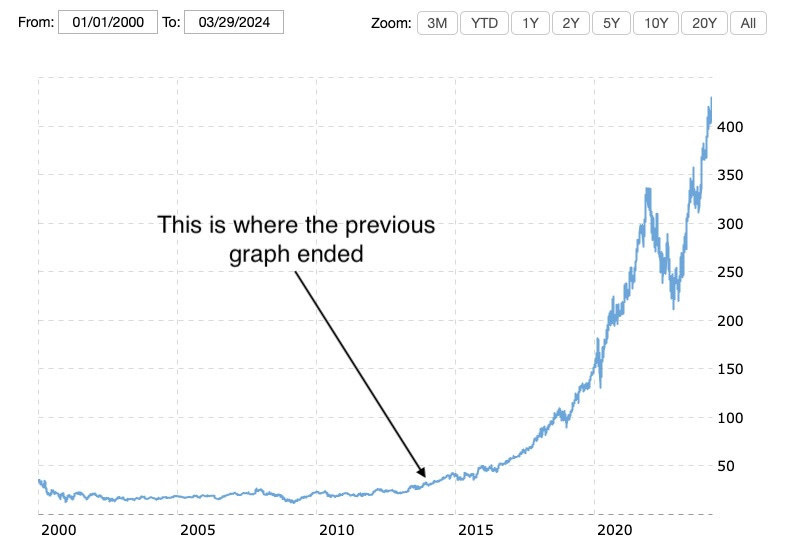

At Microsoft, Satya Nadella has engineered a corporate comeback that’s IMO rivaled only by what Steve Jobs did when he came back to Apple. Here’s Microsoft’s 21-century share price chart updated to the present:

How did Nadella accomplish this? Substack tells me that this post is getting long, so I’ll answer in the next one and talk about what I learned from him. One concept that came up during our interview, one I wasn’t expecting, was vulnerability.

Probably not as much as Welch did.

Your progeny are what your genes really care about, since they want copies of themselves to make it to the next generation. And the one after that and so on.

We Homo sapiens are about 300,000 years old as a species

And I can’t ask him; he died in 2013 at the age of 90.

If that label doesn’t bring up a lot of associations or strong feelings for you, Argyris would be happy to hear it. He was trying to avoid them and be blandly descriptive.

I’m going to keep using that phrase because I like it, and I like selling books.

As soon as I finish vetting it and gussying it up

GE had been part of the DJIA since the index was created in 1896.

1980s and 1990s were dismal for software engineers. From the top of the intellectual hierarchy at universities down, management types were jealous fake meme chasers. Engineers generally have developed management solutions for their activities. In the 1980s, engineers (incl. software engineers) could command higher salaries than the management school graduates who ran the departments they worked in. Management school graduates were generally not much more than combination secretaries / book keepers on engineering projects, even with a management title. Too many became little lying fools talking garbage about engineers. Nonsense was their business mostly. Just anything that made them feel like they deserved to have the most pay.