Silicon Valley's Most Important Innovation

If You Can Make It There, You Can Make It Anywhere

It’s AI, right? Surely, Silicon Valley’s most important innovation is AI.

No, for the simple reason that AI and machine learning aren't Silicon Valley innovations. The “Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence,” which has been called the “Constitutional Convention of AI,” was held in 1956 in New Hampshire. The proposal to the Rockefeller Foundation to secure funding for the conference (and seems to have coined the phrase “artificial intelligence”1) was drafted by four East Coasters, and its list of people interested in the embryonic field contains no Northern California addresses or organizations.

Most of the major advances in the history of AI and ML were developed far from the Valley. As far as I can tell, in fact, the first big AI innovation that came out of a Valley company (as opposed to an organization like DeepMind that was acquired by a Valley company) was the Transformer architecture that underlies much of current Generative AI. This architecture was proposed in the landmark “Attention Is All You Need” paper, published in 2017 by a team of Googlers. (correct me if I’m wrong here, please; I’m not a historian of AI).

Why NorCal and Not New England

So Silicon Valley can’t claim AI. But (foreshadowing alert) it can correctly claim to be the home of most of the companies leading the current AI boom. And Web 2.0, the Cloud, mobile computing, the online economy, the chips that power the online economy, and most of the other important things that have happened this century at the intersection of capitalism and technological progress.

It’s remarkable how concentrated the US high-tech industries are. Virtually all the largest and most valuable tech companies in the US except for Microsoft and Amazon are crammed into a tiny patch of Northern California real estate. What’s going on there?

I favor the Markoff-Saxenian-Mallaby hypothesis, which I just formulated. In his book What the Dormouse Said veteran tech journalist John Markoff takes us back to NorCal at the dawn of the computer era and shows us the improbable mix of wooly academics, campus radicals, pocket protector-wearing defense sector engineers, and frequently-tripping hippies who came together because they were all interested in these fascinating new machines. The digital (counter)culture that arose is still very much part of the Valley, as epitomized by the number of excellent computer scientists who stagger around Burning Man every year.

Sociologist AnnaLee Saxenian highlighted the knowledge-sharing and -creation benefits provided by this freeflowing culture, contrasting it with the stable, hierarchical, buttoned-down culture of Boston-area tech firms. Believe it or not, young people, there was a time when it was unclear whether greater Boston or NorCal was going to be America’s high-tech Mecca. Saxenian argued convincingly that Silicon Valley won in large part because people moved around more easily there, and hence so too did important ideas and innovations. In The Power Law, financial writer Sebastian Mallaby stresses how important the Valley’s venture capitalists have been to all that cross-pollination, and how they too left behind their their fusty East Coast peers.

Once the Valley got a head of steam, agglomeration economies kicked in. These are “the benefits that come when firms and people locate near one another together in cities and industrial clusters,” as economist Ed Glaesser puts it. When the benefits are big enough the cluster can be durable; think about New York and London for finance, or Detroit for carmaking (foreshadowing alert #2). So Silicon Valley remained Silicon Valley because most of the people who knew how to do the Silicon Valley thing of building successful tech firms were in Silicon Valley.

All the above is preamble to the main point I want to make here, a point that delivers on the promise implicit in this post’s title. To do that, though, we need a bit more preamble.

The Fundamental Fact, and What Follows

Some activities have a fundamental fact: gravity for tightrope walking, water availability for desert travel, wind for kiteboarding, the suckiness of the New York Yankees for Major League Baseball2, and so on. The fundamental fact isn’t the only thing that matters but failing to keep it in mind, even for a short time, is a great way to find yourself in a bad spot.

For digital industries the fundamental fact is Moore’s Law (in its extended version): sustained and absurdly fast improvement in all core technologies. It’s true that, as the headlines keep blaring, the original “Moore’s Law is Slowing Down:” The rate at which we can cram more transistors onto a same-cost chip has decelerated. But other rates of improvement remain robust: in bandwidth, memory, storage, power consumption, AI model capability, and so on.

Throughout the history of the digital industries, all key technologies have been improving at rates so fast that their doubling times are measured in at most a few years. I assert that this fundamental fact has never been true of any other industry (again, please let me know if I’m missing counterexamples).3 A few things follow from the fundamental fact:

In digital industries…

Product lifecycles are short, which means that

Rates of innovation must be high, and

Missing out on even one generation of improvement can be fatal.

What’s more, sustained exponential improvement means that apparently-sudden “phase shifts” occur: bandwidth to the home “suddenly” becomes fast enough to stream entertainment; capable computers get small and enough to fit into our pockets; machine learning systems start exceeding human performance, and so on.

One other fact of life in high tech is that competition is intense because potential markets are so large. And since many of these markets are winner-take-all (or at least close), coming in second is a lousy strategy.

In short, digital industries are tough places to do business — the toughest, I believe. They have uniquely high rates of change, uncertainty, and competitiveness. Sustained success in these industries requires sustained excellence in innovation, agility, and execution simultaneously.

OK, enough preamble

Here’s the big reveal (teed up by the first foreshadowing above): I think that Silicon Valley’s most important innovation is an upgrade to the company itself. This upgrade came about as high tech’s geeks grappled with their industries’ fundamental fact.

A bunch of geeks concentrated in (but not exclusive to) Silicon Valley came to believe, often through bitter personal experience, that the 20th-century playbook for running and growing a company simply wasn’t working in their world, and needed to be substantially re-written. So they did.

When I was researching my book The Geek Way I kept coming across examples of business geeks realizing that if they followed the legacy playbook built up over the last century they were going to fall behind. They weren’t going to be able to innovate fast enough, or they were going to miss an important development, or disappoint customers by delivering them things that were both late and lousy. They were, in short, going to become what Jeff Bezos calls a “Day 2” organization:

Day 2 is stasis. Followed by irrelevance. Followed by excruciating, painful decline. Followed by death.

In TGW I describe how Bezos realized that the innovation management process he designed was pointing Amazon toward Day 2 and so changed it 180 degrees, how Reed Hastings overhauled Netflix’s culture, how a bunch of frustrated programmers went away for a ski weekend in 2001 and came back with the Agile development approach, and so on.

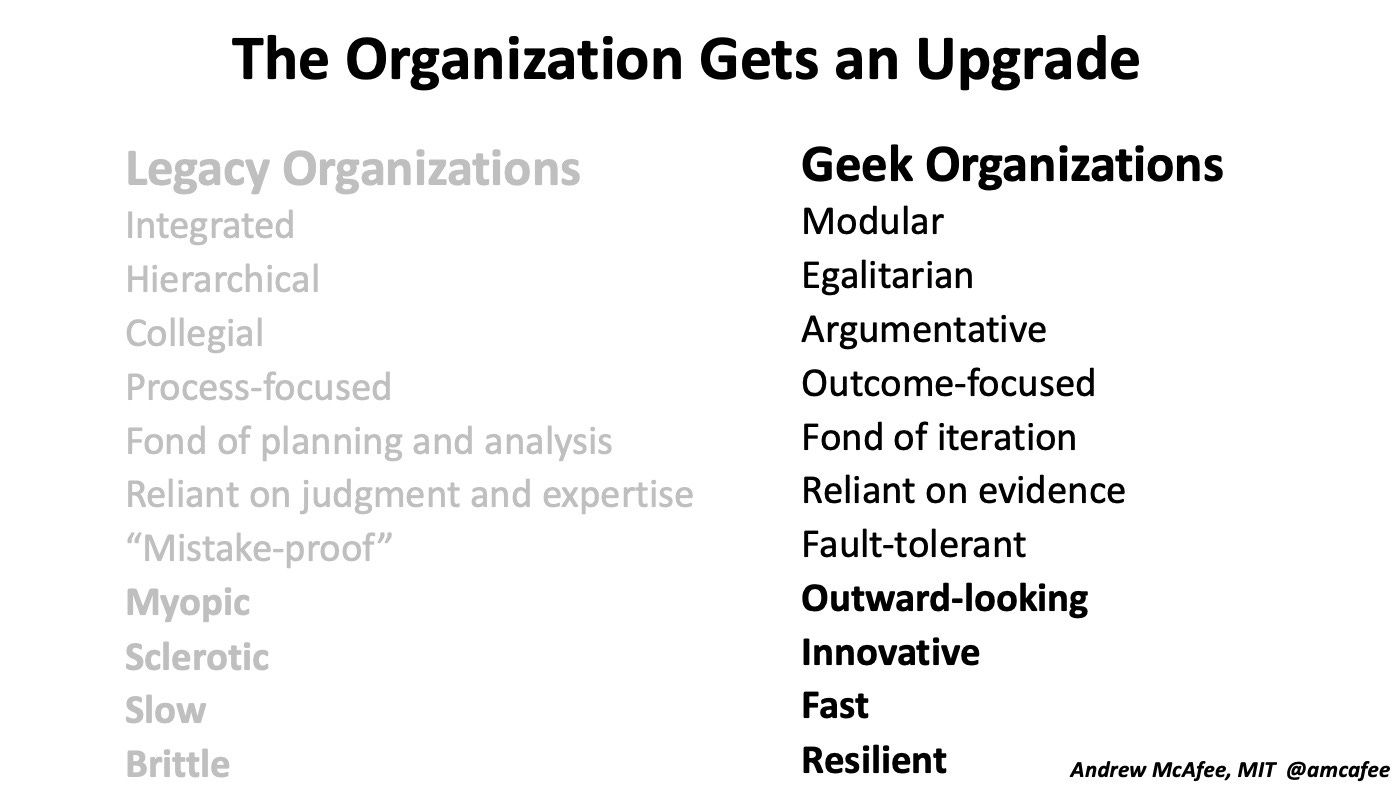

In fact, the whole book is a description of the corporate upgrade that I label the geek way, and an explanation of why it works better. Here’s a one-slide grave oversimplification summary I often use in my talks about the upgrade:

The entries at the top of each column aren't obviously good or bad. You can make an argument in favor of the legacy approach — in favor of building organizations that are integrated, hierarchical, collegial, process-focused, and so on. Over my career, I've seen plenty of practitioners and academics make exactly that argument. I might have made some version of that argument itself a time or two.

What I've come to believe though, is that building organizations with the characteristics at the top of each column makes it much more likely that they’ll wind up with the boldface characteristics at the bottom of the column (I explain why in The Geek Way (TL;DR: human nature)). And the boldface adjectives at the bottom of the left-hand column are clearly bad news for a company, while their equivalents on the right-hand side are clearly good. Which is a labored way of saying that geek organizations are better than legacy ones.

Big If True

The claim summarized on the above slide is a big one — read The Geek Way and see if I've convinced you of it — and it leads to an even bigger one. It leads to the claim that the geeks haven’t just upgraded the high-tech company; they’ve instead upgraded the company, full stop.

It’s a universal upgrade because it enables higher rates of innovation, increased agility and ability to pivot, reduced bureaucracy, and other good things while not sacrificing quality, productivity, or efficiency. These are universally valuable things in the business world.

If my claim is accurate, we'd expected to see that over time Silicon Valley would expand beyond Silicon Valley. In other words, companies and founders who came up in the unforgiving competitive cauldron of Northern California's high-tech industries would take what they've learned about building high-performing companies and apply it elsewhere in the economy. They'd bring organizations with the characteristics seen on the right-hand column of the slide above into sectors full of left-hand side legacy organizations. And quickly start mopping the floor with them.

As I've written, this is exactly what's been happening in industries as diverse as filmed entertainment, automaking (see foreshadowing #2 above), space exploration and commercialization, and defense. More industries will be added to that list in the years ahead.

I'll soon share here some visualizations about where corporate value has been created in America and around the world in the 21st century. That value creation has been highly concentrated in the geek proving ground of Northern California. It's a trend I expect to see continue and accelerate, unless the leadership of a lot of legacy companies takes bold and quick action to overcome their legacies and get themselves into the right-hand column above.

Otherwise Silicon Valley will continue to grow in economic importance because most of the people who knew how to do the Silicon Valley thing of building successful tech firms companies in any industry are in Silicon Valley.

If I had a time machine, I’d have it drop me into John McCarthy’s office as he was drafting that proposal. I’d plead with him to leave the triggering word “intelligence” out of the name of the new field he was envisioning and instead call it something anodyne like “pattern-detection computing that’s absolutely not going rise up and kill us all.”

Go Sox

It’s true that gene sequencing has improved even faster than Moore’s Law, but gene sequencing is only one of the core technologies of the life sciences. My claim is that all the core technologies of computing have been improving at rapid exponential rates for decades.

Do you believe legacy companies, like mass printers or metal producers, will change or adapt to the new ways? If so, I don't believe they have received that memo ....