Stranded Astronauts and the Biggest Disruption In Business History

OK, fine, MODERN business history. It's still a big deal.

I’ve been working for a while on a post documenting how poorly the large, successful companies of the Industrial Era have been doing as we move deeper into the second machine age and software keeps on eating the world. Then came the news of SpaceX being called on to literally ride to the rescue after an extended Boeing SNAFU in orbit. This development is an almost-too-perfect illustration of what I’m talking about. It’s “so formulaic that it could have spewed forth from the Powerbook of the laziest Hollywood hack” as Sideshow Bob put it.

To recap: astronauts Suni Williams and Butch Wilmore got to the ISS on June 8 via Boeing’s Starliner spacecraft. In a previous post, I documented how late and expensive Starliner’s development was, especially in comparison to SpaceX’s Crew Dragon. Here’s the timeline I drew of milestones for Starliner vs Crew Dragon:

This chart is still up to date, which is terrible news for Boeing. I was supposed to add the black triangle to the top timeline on June 14, when W&W were scheduled to return to Earth. Their safe return would finish Starliner’s much-delayed certification process and give Boeing the green light to start doing paid crewed missions for NASA (and perhaps others). But thruster problems encountered on the trip up to the ISS proved hard to diagnose and fix, and on August 24 NASA announced that the astronauts would be coming back with SpaceX in early 2025 even though they went out with Boeing. This was not great news for them since they’d have to stay on the ISS for more than half a year longer than they’d planned.1 It was also, of course, seriously grim news for Boeing.

Here (and here and here) and in my book The Geek Way I’ve written about how other Industrial Era incumbents (IEIs) have been brought low: GE, VW, Warner Bros, and so on. And how a new crop of geeky young West Coast companies has made these and other IEIs look bad on their own turf. Here I want to document just how big, broad, and unprecedented the geeks’ disruption of the business world is. So let’s look at a century’s worth of competition and value creation among the biggest US companies.

The American Century

By the mid 1920s American capitalism was set to do its thing. The US had become the world’s largest economy in the1890s and kept going strong in the new century. Our land was rich in raw materials and our population was large, growing, and in need of victuals, manufactures, and other things to buy in shoppes.2 America’s infrastructure and capital were unscathed by WWI, and our workforce was big and increasingly educated; by 1918 every state mandated at least elementary school for all children.

One other important factor: As was the case in the other large industrialized countries of the West, a new kind of business organization had taken shape in America by the 1920s. This was the company we’re now accustomed to: big, complex, professionally-staffed, and full of people working in offices coordinating stuff. Alfred Chandler, who just about invented business history as a field of study,3 documented how a “managerial revolution” started in the middle of the 19th century in response to the challenges and opportunities created by big markets, powerful technologies like the steam engine and telegraph, economies of scale, and ever more complicated products and supply chains. Small family firms gave way to large professionally-managed ones,4 some of which became so big and powerful (and maybe a bit more interested in colluding than competing?) that Teddy Roosevelt went after them in a “trust busting” spree that included more than 40 lawsuits during the first decade of the 20th century. There were still plenty of big American companies in the wake of that spree.

Business As Usual, Despite All That

The decades after 1926 weren’t especially calm, were they? I don’t think you’d characterize them as an extended period of stasis for private enterprise. A lot happened that could trip up an established company or provide opportunities for upstarts. There was a great depression followed pretty quickly by a world war, for example. Then there was suburbanization, the rise of mass media, and all the upheavals of the sixties. And two more foreign wars, in Korea and Vietnam. There were LBOs, Wall Street barbarians at the gate, foreign competitors at our shores. We deregulated and entered the Atomic Age and the Space Age.

Also, the managerial revolution kept unfolding. There was total quality management. There was management by walking around. There was yield management. Some bold innovators even got rid of the word “management” when naming their movements and went with names such as “Six Sigma,” which sounds like something out of the Marvel Comic Universe.

In summary, there was a lot. And it’s remarkable how little all of it mattered.

I mean “mattered” in a narrow sense, but an important one: did any of these developments change the age cohort of America’s top companies?

Of course the names at the top of the list of the country’s most valuable companies changed year by year, but did the average age of those top companies? Or did the old dogs in the pack keep learning the new tricks? I got interested in this question because of my belief that we’re living through a turning point in business history — one characterized by deep and rapid change of a type that will be hard for IEIs, even historically quite successful ones, to master.

In other words, I’m making a big claim: a bold new chapter in managerial capitalism is at hand! I need to support it.

One way to support it (certainly not the only one) is to

go back to the earliest year for which we have good, comprehensive data about US public company valuations, which is 1926.

Identify the 50 most valuable companies that year. (Why 50? I’m following the Cool Hand Luke rule: 50’s a nice round number.)

Determine when those companies were founded.

Calculate the average founding year for the group, weighted by market cap.

Repeat steps 1-4 for every subsequent year up to the present.

Draw a graph of the results.

See what story that graph tells.

When Old Dogs Finally Meet New Tricks

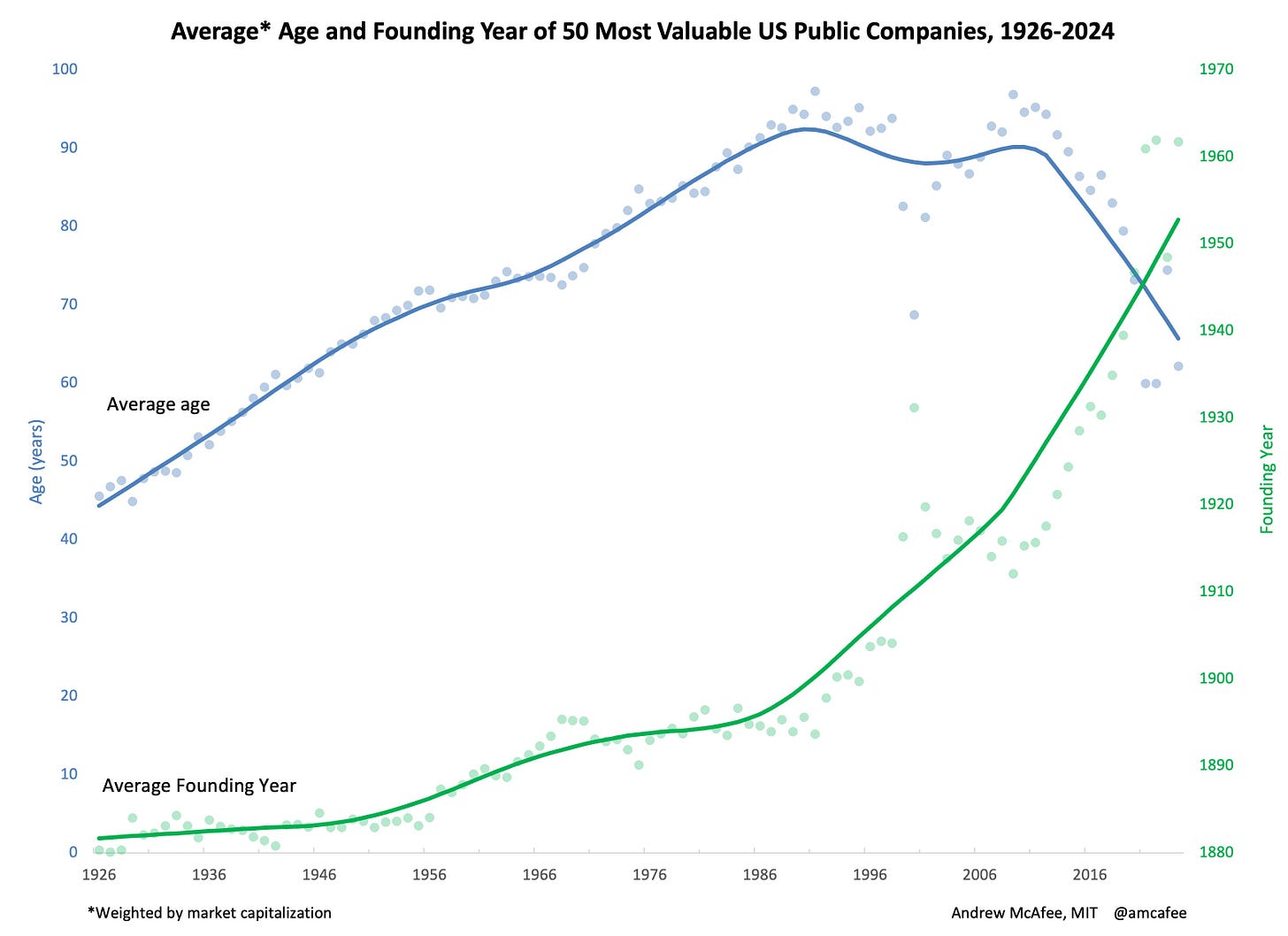

The graph I drew is below. It shows the weighted-average founding year of the top 50 most valuable US public companies over the period 1926-2024 in green. The blue line uses the same data to show the average age of the top 50.

I find the blue line easier to interpret. It tells a three-chapter story about American big business over the past century.

Chapter 1, which lasts for about the graph’s first six decades, is a tale of steady aging at the top. It’s emphatically not a tale of age-related competitive decline — of big companies doing fine until they’re 60 or 80 or however many years old, then fading from the top ranks because they couldn’t keep up any more. My strong guess is that during that time big US companies did slow down some as they aged. They became more bureaucratic, risk-averse, and so on. But because of their economies of scale, access to financing, established relationships, and so on those declines weren’t enough to knock them off the top of the charts.

During Chapter 1 the graph’s green line shows uninterrupted dominance by a cohort of companies founded well before 1900, on average. It’s not surprising that companies of that vintage would be on top in 1926, but I do find it wild that a similar vintage continued to be on top six decades later.

Chapter 2, which according to my eyeballs lasts about 20 years from 1986(ish) to 2006(ish), looks like a tug of war between the IEIs and some group of younger companies. The average age of the top 50 flatlines, which means that the average founding year increases steadily. There’s a short, sharp discontinuity in the late 1990s as a group of very young tech companies became very valuable. But then the dot-com bubble burst and the Y2K false alarm scare passed, tech valuations withered, and the lines went back to where they had been, more or less. The top 50 were old — they averaged out to be at least octogenarians throughout chapter 2 — but they stopped getting older as a group. There was some kind of youth movement challenging the IEIs for the first time. And the early 1990s we hit a milestone: the average founding year of the top 50 entered the 20th century.

In chapter 3 the tug of war turned into a rout. For the first time the top 50 got steadily and quickly younger. Between 1926 and 1986 the trend was for the top 50 to age by an average of 0.75 years every year. Between 2006 and 2024 they got younger on average by 1.25 years each year. A whole lot of very young companies entered the top 50; in 2024 the group was as young as it had been 75 years earlier.

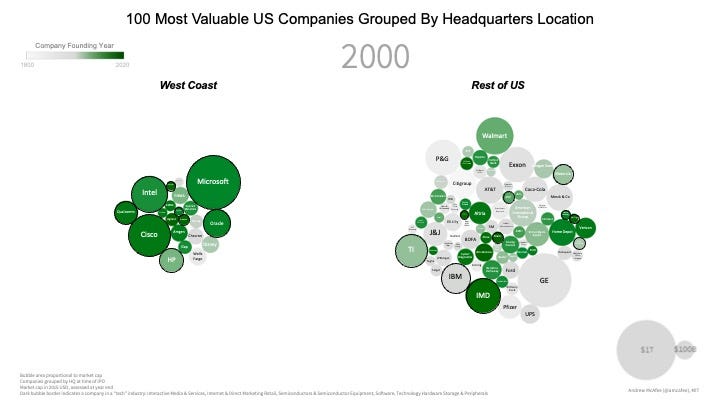

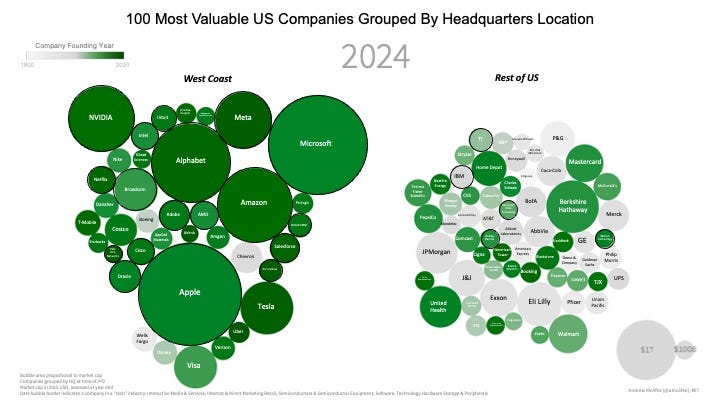

Who are the whippersnappers driving down the average of the top 50 these days? As I said above, they’re geeky young West Coast companies. To show this, here are a couple graphs I drew5 for other purposes. Their dates don’t line up exactly with the chapters described above, but they convey just how much value creation has shifted among big US companies, and in what direction, during the 21st century.

Here are the 100 most valuable US public companies at the start of 2000, divided into two bunches: West Coast, and the rest of the country. Each company is represented by a bubble, the area of which is proportional to its market cap at the start of the year. The greener the bubble, the younger the company. Companies in “high tech” industries have bold borders on their bubbles.

And here’s the same picture at the start of 2024:

Managerial Revolution 2.0

As these visualizations show, the rise of hugely valuable suppliers of digital technology is a big part of the story. But I believe that concentrating on them obscures an even bigger story — the story of a second managerial revolution.

My first post here included a quote from sharp thinker, legendary investor, and gigantic geek Steve Jurvetson. Here it is again:

“Any company that thinks they’re not a software company is not long for this world, because the agile way we’ve learned to build software is becoming the agile way we build everything. I sometimes feel like I have a sixth sense. I can see dead companies. They don’t know they’re dead, but they’re dead because they’re not responsive enough. And the companies that iterate more quickly will just run circles around them. They’re innovating every couple of years on something that you might take seven years to do.”

Jurvetson is succinctly making a two-part claim: that the company has received an upgrade, and that IEIs who don’t, won’t, or can’t install this upgrade are in a world of trouble. I agree with him intensely enough to have written a whole book giving my explanation of what this upgrade consists of, and why it works so well. I call the geek way, and believe it’s a change in how to run an organization as big as the one documented by Chandler.

So far Boeing looks to be in the “don’t, won’t or can’t” category, and its latest humiliating setback is having to rely on geek exemplar SpaceX to salvage a job it botched. This is an especially vivid demonstration of what happens when geeks go up against IEIs, and it won’t be the last one.

Please Prove Me Wrong

Here’s a prediction I want to be wrong about: the average age of the top 50 most valuable US companies is going to continue to decrease in the years ahead. I want to be wrong about that because I want the IEIs — the old dogs — to get their mojo back and start being real competitors to the young geeky upstarts that are currently making them look bad. We know from Microsoft’s example that such a comeback is possible. But it’s hard, requiring Nadella-level commitment and energy from the top. I truly hope I’m wrong about how many IEIs will summon that level of commitment in the years ahead.

There are no washing machines in space and W&W only packed for a short trip, so it looks like they’re going to be wearing the same underwear for a long time.

I learned when researching my book More from Less that America’s rapid industrialization in the latter half of the 19th century helped drive the bison to the brink of extinction. Why? Because at that time power was transmitted throughout factories by leather belts, and bison leather was the toughest available. According to one estimate, “almost 1.4 million hides were sent east on three railroads between 1872 and 1874, and that because of losses to wolves and incompetent skinning, each hide actually represented five dead bison.”`

Chandler was the kind of patrician Yankee scholar common, I imagine, on Ivy League campuses when Ike was president. I met him a couple times when I was a doctoral student. His knowledge was vast, his manner courtly, his bearing erect, and his wardrobe tweedy.

A fascinating recent paper finds that the lack of Chandlerian middle managers is one of the factors holding back the growth of large companies in many parts of the world.

My excellent RAs Roy Reinhorn and Ori Zilka actually drew this one. It was a lot of work.

I wonder what the collation is for finance types becoming CEO's of companies and how that hastened their demise? Look at General Electric. Jack Welch was the worse thing that happened to it. Ditto Hewlett Packard. Engineers replaced by bean counters, profits work for a while due to financial magic then they are toast. Westinghouse, a shell of the former company with now limited expertise. Boeing, well, enough said. The younger companies are more like the old ones at their peak: they know their customers and they know their products because they could build them. So you could say the worse thing to happen to business is the rise of the MBA?

This is fascinating. As always Andy has a really perceptive focus on something pretty big