The Long Goodbye? Incumbent Competitiveness in the 21st Century

Beer Leagues and Green Bubbles

A lot of the iconic American companies of the 20th century seem to be having trouble in the 21st so far. GE has been sold off for parts. Boeing is in shambles. Intel just got delisted from the Dow Jones Average (and probably called up GE to talk to someone who knew what that felt like).

In many cases the troubled giants are being outpaced by a much younger rival. NVIDIA, not Intel, is making the must-have chips for the unfolding AI revolution (and is today the most valuable company on the planet). It was bad enough when Boeing lost NASA’s confidence that it could bring home astronauts safely from the ISS. It was worse when SpaceX was given the rescue job. America’s legacy automakers last year sold fewer than 150,000 electric vehicles in the country, while Tesla sold more than four times that amount.

Over and over again, the incumbents underestimated their challengers. A decade into the 21st century Time Warner CEO Jeff Bewkes perfectly encapsulated the insouciance of the corporate establishment. When asked in 2010 if he was concerned about Netflix’s growing importance within the entertainment industry he responded “It’s a little bit like, is the Albanian army going to take over the world? I don’t think so.” Netflix CEO Reed Hastings started wearing Albanian army dog tags, and started dismantling Hollywood’s establishment. It didn’t take long. Netflix is today worth almost $380 billion. Warner Bros Discovery, the current incarnation of the studio plus CNN, HBO, and other household names, is valued at less than one-fifteenth that.

Am I cherry-picking here? Am I ignoring cases where the American corporate dreadnaughts of the 20th century have done just fine in the 21st? Have created a ton of value while making short work of the young punks who tried to encroach on their turf?

Let’s take a look.

The Stable Columns of the 20th Century

Let’s look at the 50 most valuable public US companies, and see how they’ve changed since 1930 (which is about as far back as we have good data on valuations). We’ll concentrate on when each of the top 50 was founded, and how that distribution of founding dates (that is, company ages), has changed over time. I looked at this phenomenon in an earlier post; here I want to add some more detail to the picture.

Below is the picture from 1930-1990. A column of bubbles marks the start of each decade. Every column has 50 bubbles, corresponding to the 50 most valuable companies at the time (that is, January 1 of 1930, 1940, and so on). The area of each bubble is proportional to the company’s share of total top 50 market cap. So each column has 100 “units” of area, which are spread across its bubbles based on how valuable the corresponding company is.

The position of each bubble on the y-axis gives the founding date of the company, with older companies at the bottom. To make this visualization clearer, all companies founded earlier than 1840 are included in the 1840 bubble. An orange line traces the weighted-average1 founding date across columns.

This visualization shows a remarkably stable cohort of large American companies over six decades. GE, GM, and AT&T are all there at the start, and at the end. The 1840-and-earlier bubble, which contains companies like JPMorgan that were at least 90 years old in 1930, is still pretty big 60 years later. The only significant “new” bubble to arrive during the time shown above is IBM, which essentially created the American computing industry and dominated it for decades. Whatever regulators think of near-monopolies in large and growing industries, investors love them; in 1970, IBM was responsible for fully 15% of total US top 50 market cap. Its bubble is green to mark it as a “high tech” company — one that sells hardware and/or software.

Big Blue2 was a relative newcomer to the US top 50. It was founded in 1911, while most other big American companies of the 20th century were started in the 19th. As recently as 1990, the weighted-average founding year of the top 50 was earlier than 1900. A World War, a Depression, stagflation, Woodstock, an oil shock. and other things that a songsmith like Billy Joel would be able to combine into earworm lyrics didn’t much rattle the top 50. The throng remained the same.

The companies in this throng remind me of participants in beer league hockey, taking the ice against familiar faces week after week. There is competition in this league — and there might be different teams on top year by year — but the stakes aren’t life or death.

The 1990 column shows a few new entrants in this league: companies founded after the end of WWII. The youngest of these is NYNEX, formed out of the breakup of AT&T. The oldest, and the only green bubble so far that’s not IBM, is Digital Equipment, which gave us New Englanders hope that the Northeast would become a high-tech hotbed. But this was not to be. Tech companies based in the land of sleet and Puritans did pretty well as long as computers were kept in special rooms and tended by a nerdy priesthood. Once these devices started to spread and get personal, though, New England fell behind. The region just couldn’t wrap its mind around the democratization of computing. As Digital founder Ken Olsen is said to have said “There is no reason for any individual to have a computer in their home.” It will not surprise you to learn that his company’s dot doesn’t reappear in our graph after 1990.

Attack of the Green Bubbles

But a lot of other green dots do. Here’s the graph with columns added for the decades since 1990, along with a bonus column representing the situation at the start of 2024:

It’s like a bunch of hockey teams full of young players showed up and started skating circles around the veterans, exposing how much their skills had declined (or, at best, stagnated) after long years of playing mainly against each other. Value creation among American big businesses became strikingly concentrated in the 21st century, and largely left out the giants of the 20th. In 1990 companies founded after the end of WWII were responsible for only 8% of total top 50 market cap. In 2024, the equivalent figure was 77%. The incumbents of the 20th are fading and an entirely new cohort, the most prominent members of which are not yet 50, is taking over.

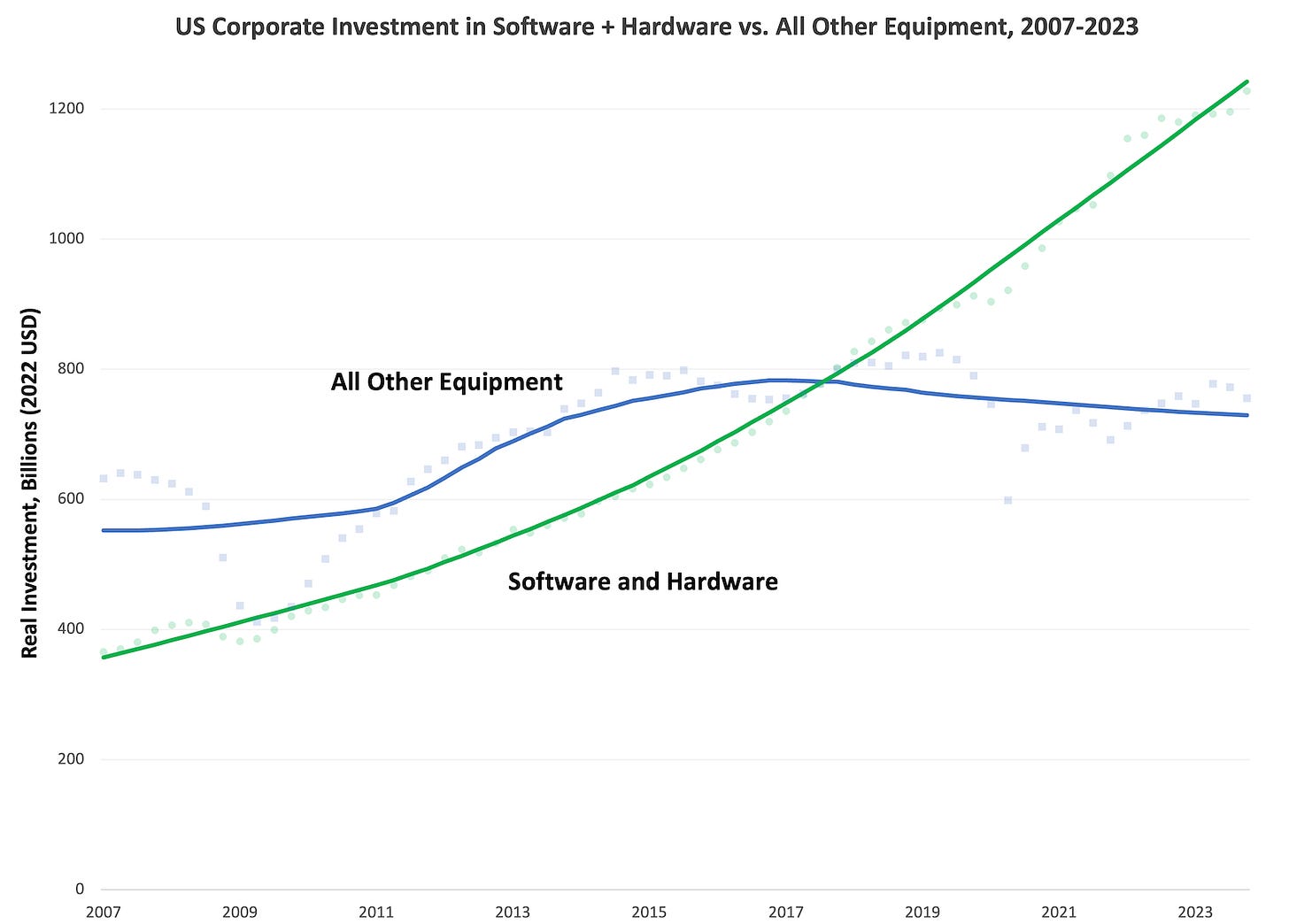

The members of this new cohort are doing two things. The more obvious is that they’re selling technology during a sustained boom in buying technology. Below is a graph showing US real corporate spending on equipment from 2007 to 2023. It breaks this spending into two categories: digital equipment (that is, software and hardware) and all other equipment — all of the drill presses and warehouse shelves and bank vaults and pizza ovens and so on needed throughout the economy.

Corporate America’s thirst for all things digital has been growing at a nice smooth exponential rate3 that brings great joy to many of those big green bubbles (like NVIDIA and Microsoft). But not all of them. Meta, for example, sells virtually no digital equipment to corporations.4 Instead, it sells ads to advertisers. Its bubble is green because of quirks in how we categorize companies into industries.

This arbitrariness in classification masks the other thing that all those big new 21st-century green bubbles are doing. In addition to making and selling digital equipment, they’re also entering and disrupting many industries far away from the traditional “high tech” sector. My off-the-top-of-my-head list of these industries includes retail, advertising, recorded music, print journalism, filmed entertainment, consumer electronics, photography, and urban transportation.

As I’ve written here, here, and here, young companies with a whole lot of Silicon Valley DNA are also now challenging incumbents in classic metal-bashing industries like automobiles, space, and defense. These challengers are classified outside the computer and information industries (as they should be) so their bubbles aren’t green (Tesla’s isn’t), but that’s a distinction without a difference. Virtually all the big new bubbles appearing this century are part of the same phenomenon: deep and fast disruption to industry after industry caused by young, techy, Silicon Valley-ish companies showing up and outplaying the veterans that have been there for quite a while.

In future posts I’ll dive into why this disruption is happening (TLDR: unclear, but Moore’s Law and hippies probably matter), whether it’ll continue (yep), and what effect AI and Generative AI will have (they’ll likely accelerate the disruption). Here I just wanted to document the phenomenon and let the incumbents of the 20th century know that their beer league is likely to be crashed by bunch of flashy new teams before too long.

Weighted by market cap

Maybe I should have made the high-tech bubbles blue?

I predict that corporate thirst for digital gear will continue to grow in the years ahead. After all, this graph stops just as the Generative AI boom was starting.

Despite all the money the company spent on the Oculus headset and other aspects of the still-nowhere-to-be-seen “metaverse.”

Nice article, and I Iove the graphic.

I think analysis of how the list of largest corporations have changed over the last two centuries is a type of economic history is highly underdeveloped.

i think both this analysis and discussion superb....that said, i would highlight that the 'leaderships' of these legacy firms/incumbents appear to have little coherent command of the differences and distinctions between 'infrastructures' and 'sunk costs;' even worse, their willingness and ability to invest in their customers and privilege 'Customer Lifetime Value' over 'Sales' as a strategic/financial KPIs pretty much assured that they doubled down on what they were doing rather than (re)position themselves for what's next....the most successful firms tend to have the most successful customers and clients.....whether that's correlation or causality, i'll leave to the bayesians and pearl-ians