US v EU in Tech: A Tale of Two Gaps

And one Fireside Chat

Steffi Czerny, the German national treasure who’s the doyenne of the DLD conference, gave me the stage there last month for 12 precious minutes. I decided to use them to continue the conversation sparked by last fall’s Draghi report on EU competitiveness. In it, Draghi drew attention to the comparative weakness of the region’s technology ecosystem. I followed his lead and wrote a couple posts here on that topic.

As I was mashing together slides, thoughts, and graphs for DLD I realized that I was looking at a tale of two gaps, and two non-gaps. So that became the theme of my talk (even though as you see below the DLD folk labeled its video using the title I gave them before I had my “two gaps” moment of inspiration).

No Biggie

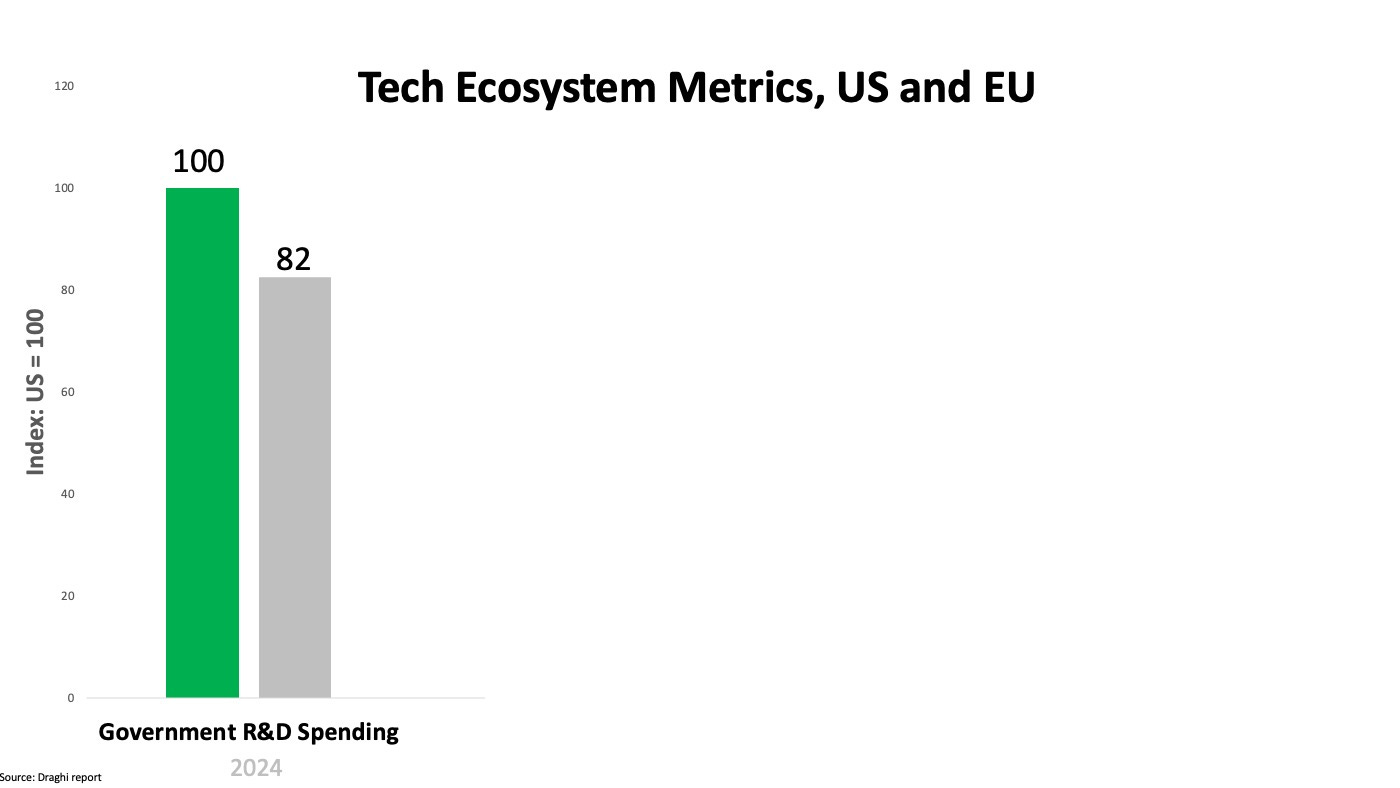

The first non-gap (Or, to be a bit more accurate—non-huge gap) is between government R&D funding in the US vs. the EU. As Draghi points out, total EU funding is within 20% of US levels:1

Government support for R&D has many aims. One of them is to yield innovations that can be brought to market. In recent decades, venture capital has emerged as a critical element of that process — maybe even the critical element. In his great book about US venture capital, The Power Law, Sebastian Mallaby makes a strong claim (and one that the book amply backs up):

Venture capital has stamped its mark on an industrial culture, making Silicon Valley the most durably productive crucible of applied science anywhere, ever.

Mind This Gap

Let's say that Mallaby is correct that venture capital is a vital catalyst in the crucible of applied science. Then the EU has a big problem, because there’s a big gap in VC funding between it and the US:

A Decent Unicorn Nursery

Downstream of VC funding in a well-flowing stream of commercialized innovation are unicorns: private companies (usually in high-tech industries) valued at a billion dollars or more. There are few if any US tech unicorns launched without VC backing, and I strongly suspect the situation is the same throughout the world.

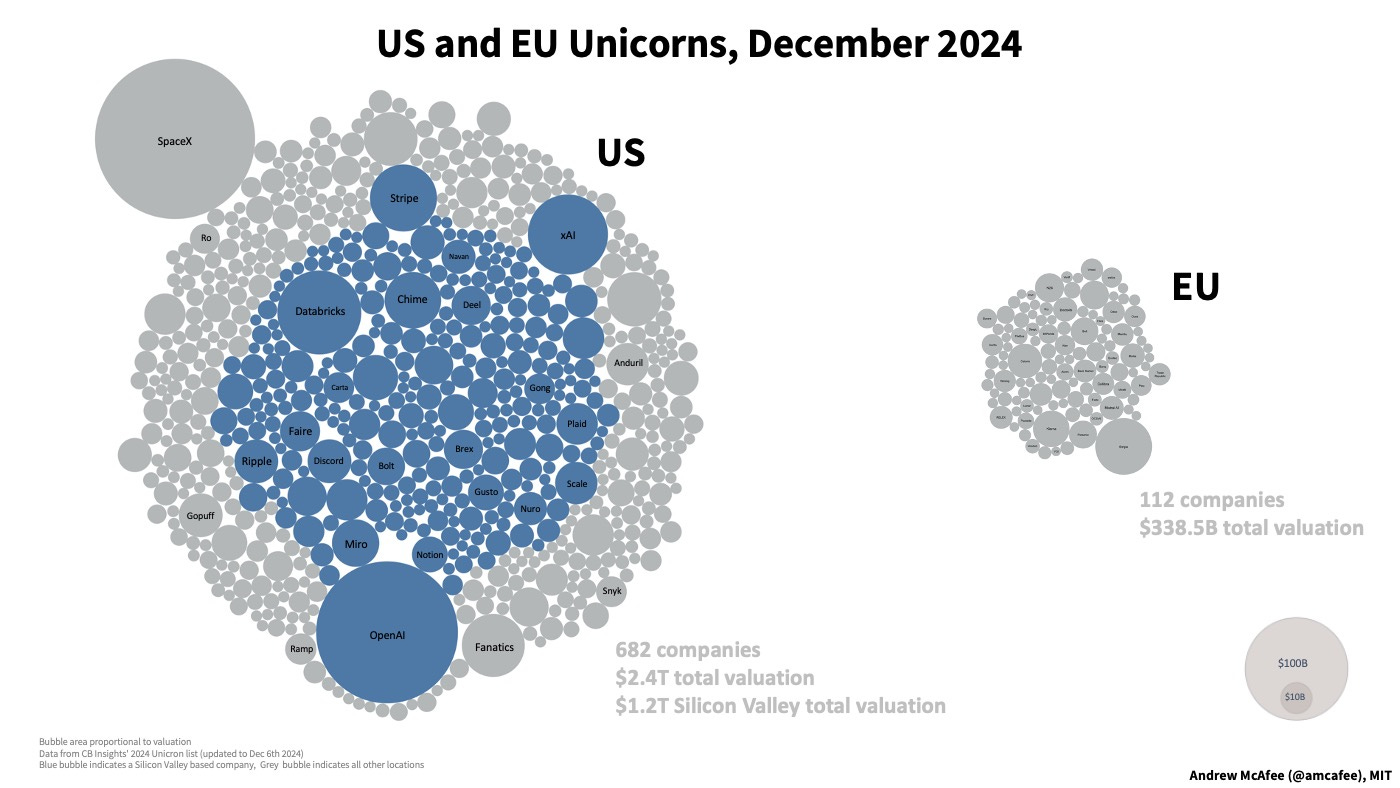

Data collected by CB Insights let us compare the number and value2 of current US and EU unicorns:

There’s a big difference here, but it’s not much bigger than the difference in overall VC funding shown above. If EU VC funding is at about 20 compared to the US, total unicorn valuation is at 14:

The US VC ecosystem is better at turning a dollar of VC investment into a dollar of unicorn value, but not wildly better.

In Public Markets, a Birth Dearth

Before my European readers start celebrating, however, let me show one final gap. Spoiler alert: it’s a huge one.

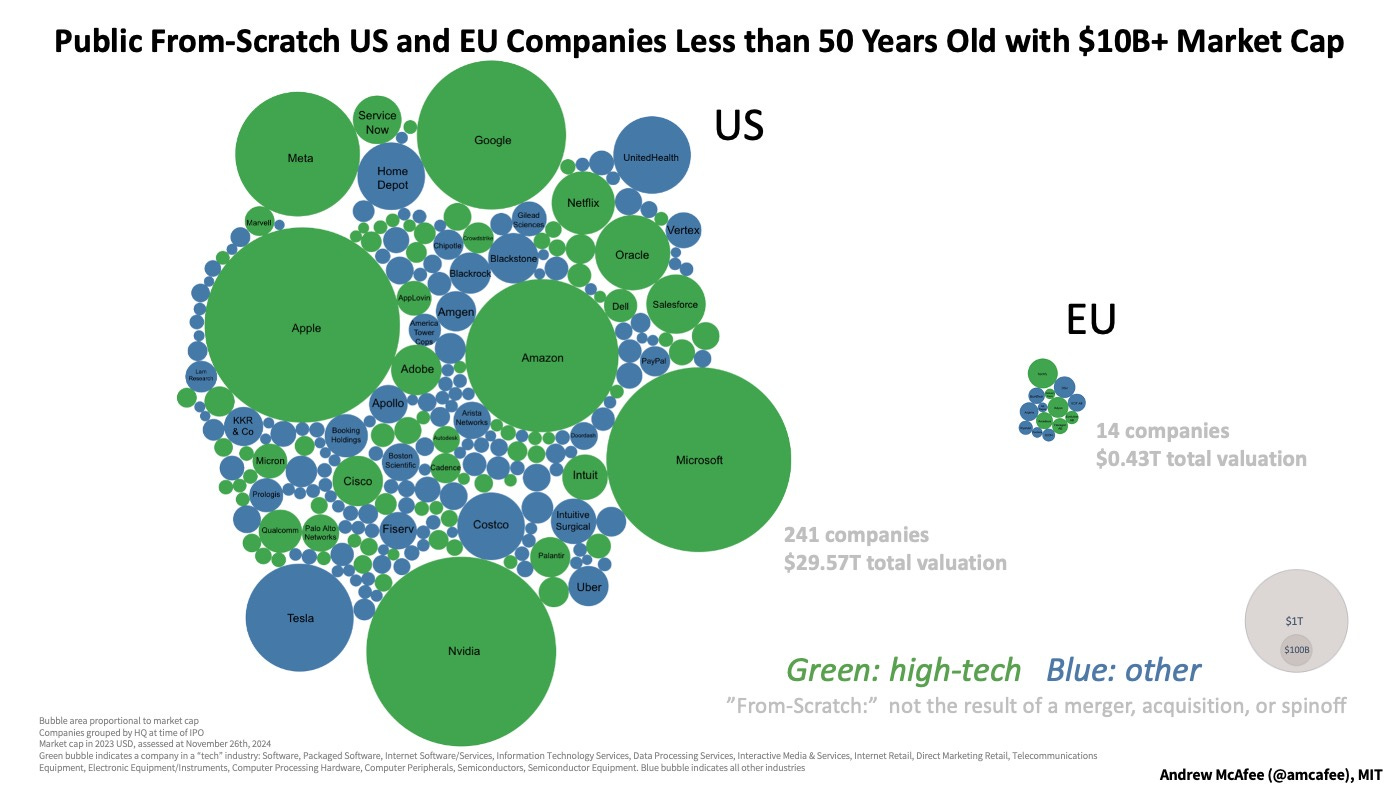

One thing we3 want is for unicorns to grow up into large young public companies. But Europe isn’t doing a great job here. As Draghi pointed out, “there is no EU company with a market capitalisation over EUR 100 billion that has been set up from scratch in the last fifty years”4 In an earlier post here I took that threshold down one order of magnitude and looked at the population of from-scratch companies in the US and EU worth at least $10 billion and less than half a century old. Here’s the latest visual comparison of that difference.

Everyone, this is a huge difference. By one calculation it’s fully ten times bigger than the difference between the two regions’ total unicorn value:

This gap analysis helps focus our attention. If we want a thriving EU tech ecosystem (and as a member of team Liberal Democratic West I definitely do) we should work on closing the VC funding gap, and the gap in turning unicorns into valuable young public companies. Which is saying the same thing twice.

Remove the barriers to creating super valuable new public tech companies and the VC will show up in droves. Once they show up, they’ll catalyze more such companies; that’s their métier. A virtuous cycle will be born, and the gaps will start to close.

But won’t it be both expensive and difficult to start that happy cycle? No.

According to Mallaby, it’s pretty straightforward to create a healthy VC sector. And mirabile dictu, it’s also cheap! Governments don’t even have to subsidize venture capital. As Mallaby writes in The Power Law “In most cases, four simple steps will pay off more [than VC subsidies}. Encourage limited partnerships. Encourage stock options. Invest in scientific education and research. Think globally.”

For the EU to start seeing valuable young from-scratch public companies, I’d add one more step: roll back burdensome tech regulation. From GDPR through the AI Act, the region has been stifling innovation and discouraging entrepreneurs and venture capitalists. I don’t see how a European tech ecosystem blooms until the thicket of regulation is cleared.

On my recent swing through Europe, however, I didn’t get the impression that the above changes were afoot. Or even top of mind for the EU’s policymakers. At DLD, I had a fireside chat with Robert Habeck, the current German Minister for Economic Affairs.5

I’ll close this post with a transcript of the chunk of our conversation devoted to getting more venture capital in the EU (this chunk starts at the 12:38 mark in the video). I wish I found more grounds for optimism in his thoughts on the subject.

AM: You and I, in our [opening] remarks, both brought up something else that is not working as well as it probably should be in the EU right now, which is private venture capital investment.

If you and I come back in five years and have this conversation again, and there has been a huge leap—a huge increase in venture capital investment in that five years—why? What will you do to bring it about, to increase it a lot?

RH: first, a lot of companies have a lot of data. As I pointed out, the technique of the last century—automotive, machinery, and so on—we had a very, very strong position. It's not that there’s no competition. Tesla and the Chinese car industry, of course, are strong competitors, but the data is there. If the fight about ChatGPT is lost, I don't know. Maybe the race is lost, but all the other artificial intelligence programs can still be developed in Europe.Therefore, we need our own approach. We don't have one big European automotive company, but we have several—twenty or so. We should combine them, bring them together, and shape an open-source system. Then the companies can learn from each other without losing their data. This is a very specific European approach, but this is the way forward.

Then, of course, we need to scale it up. That is what we tried, but maybe not successfully until now. What's going to be different in the future? Well, I accept that, other than the American money market, the German or European money market is too small. It's fragmented. You're right—we need a Capital Market Union. The discussion has been going on for maybe ten years or so. This takes too long—everything takes too long.

AM: But to be a little more specific—think of the top ten venture capital firms in the world right now. Relatively few of them have a sizable presence in the EU. What will it take to change that?

RH: Well, first of all, the Capital Market Union is about ensuring that banks in Europe can lend to each other on the same system. The political problem is that the debt rate in Europe varies significantly. Germany has only 60%, while Italy has—I don’t know the exact number—maybe 150%? France, 120%. This is without considering their nuclear fleet, which is also a state company, adding another 50 or 60 billion as debt to the state budget.

Therefore, countries with better fiscal situations are hesitant, fearing they would have to guarantee for the weaker banks. That’s why everything takes so long and becomes so complicated. But as a German, I can say from our own history: if Germany is willing to go a little bit further than our own short-term interest, then Europe moves forward. It will be up to the German government to make the Capital Market Union and banking union happen. This will only work if we do a little more than we believe is in our immediate self-interest, because in the long term, the greater interest comes back to benefit us.

Germany has to lead from the second row—not by forcing everyone to do exactly what we do in our banking system. That’s not going to happen. France, Italy, and others cannot simply adopt the German model. But we can help facilitate the change and create a more prosperous European economy. This benefits Europe as a whole.

This is something I actually learned from the conservative chancellors of the past. I never voted for Helmut Kohl, and I wasn’t born when Konrad Adenauer was Chancellor, but that was always the way forward. They pushed back short-term German interests a little, and then Europe developed. It leapfrogged to the next step. The invention of the euro is an example of something similar. Germany guaranteed with its own Deutsche Mark, which was one of the strongest symbols of economic stability in Europe. That kind of leadership made European integration possible.

That was the end of our conversation. But not, I hope, of the conversation about the EU’s tech ecosystem.

I got the EU number wrong in my talk. The graph included in this post has (I hope) the right number from the Draghi report.

As of the most recent funding round

“We” here are people who like a large, vibrant, innovative high-tech sector.

I beg you, before you bring up ASML please familiarize yourself with Draghi’s definition of from-scratch: ““From scratch” refers to starting a company from its inception as a new entity, rather than through mergers, acquisitions or spinoffs from established firms.” ASML is the result of a merger.

I say “current” because Germany is having federal elections on February 23.

Your analysis was poignant and I often use your graphs to alert people to the reality of European decline. Most people here aren’t even aware of the Draghi report and the visuals are a nice shortcut to the necessary emotional punch. The verbose emptiness of Mr. Habeck’s replies is shocking and I wish he were the only inept politician in charge of a European economy, but we look in vain for inspiration in this field.. People who don‘t understand economics should never be in government and certainly never be in charge of economic development anywhere.

Most EU countries have HORRIBLE tax law relative to private company equity/stock. Getting equity to be culturally accepted as compensation is hard enough with good tax structure, but with the need to pay cash on illiquid startup equity (looking at you Italy) it's impossible.